Fruit-For-All is a game by ARQTEQ that puts players in a battle of wits to achieve thier ever-changing secret objectives using a twist on Rock, Paper, Scissors.

Each round, players get a new objective and spend a little time trying to persuade others to take the action that will help them reach their objective. Some objectives are about cooperation while others are about trickery.

Every player has the same set of five action cards. Once everyone says they have decided which card they will play in a round, each player selects one of their cards face down. Then, everyone reveals their choices simultaneously.

When an attack hits a player, that player loses a life. The last player with lives remaining is the winner.

This is one in a series of seven articles outlining my judging decisions for the finalists in The Game Crafter‘s social deduction game design challenge. You can see the full article list here.

Visit Gamified Content’s YouTube channel to watch my review of Fruit -For-All’s shop page from the semi-finalist judging round.

High-Level Review

This contest brought out some interesting discussion with other game designers about what truly defines a social deduction game.

Many of us came to agree that, while bluffing is an aspect of social deduction, bluffing on its own does not create the full social deduction experience. Instead, players need to have an enduring role through the game arc. While it’s possible for this role to change mid-game, that change cannot be random. Some kind of action other than a random card draw must initiate it.

I also think teams are important for bringing out the need to read others and watch what you say. Knowing other players can win along with you means believing and cooperating with the right people can help you win.

After playing all the finalist entries, I’ve come to feel that games like Coup, Mascarade, or Outlawed are probably more appropriately labeled as bluffing games instead of social deduction. While someone who enjoys social deduction may be likely to enjoy these bluffing games, they are not fully the same type of experience.

This being said, while this design challenge was taking submissions, I specifically listed Coup as a valid example of a social deduction game on the contest page, so I did not disqualify the entries that fell more to the side of bluffing than social deduction.

Fruit-For-All was one of the challenge entries that felt much more like a bluffing game than a social deduction game.

In the end, though, it was the only finalist that I gave full points to for “would play again.” (Although I do believe many of the other finalist could get there with a bit more development.)

I think there are a couple of places where Fruit-For-All’s rules and card text could use a bit of clarification, but, overall, this game feels the most fun, smooth, and publish-ready of any of the finalist entries. The art is fun and appealing, it’s easy to teach and set up, and the negotiation before the simultaneous card play is amusing.

The player elimination was the biggest drawback in this game (and it can happen pretty early), but the game is short enough that it’s not a huge issue.

Components

The game comes in a 108 card tuck box. Since the game only has 90 cards, the extra space left inside the box made it easy for the box to get a bit bent and warped. Within one day of opening the box, it was too bent to stay fully closed.

I love how affordable and compact tuck boxes are, but it’s important to fill them with the exact amount of cards they are made for to provide the structure needed to keep them from getting bent.

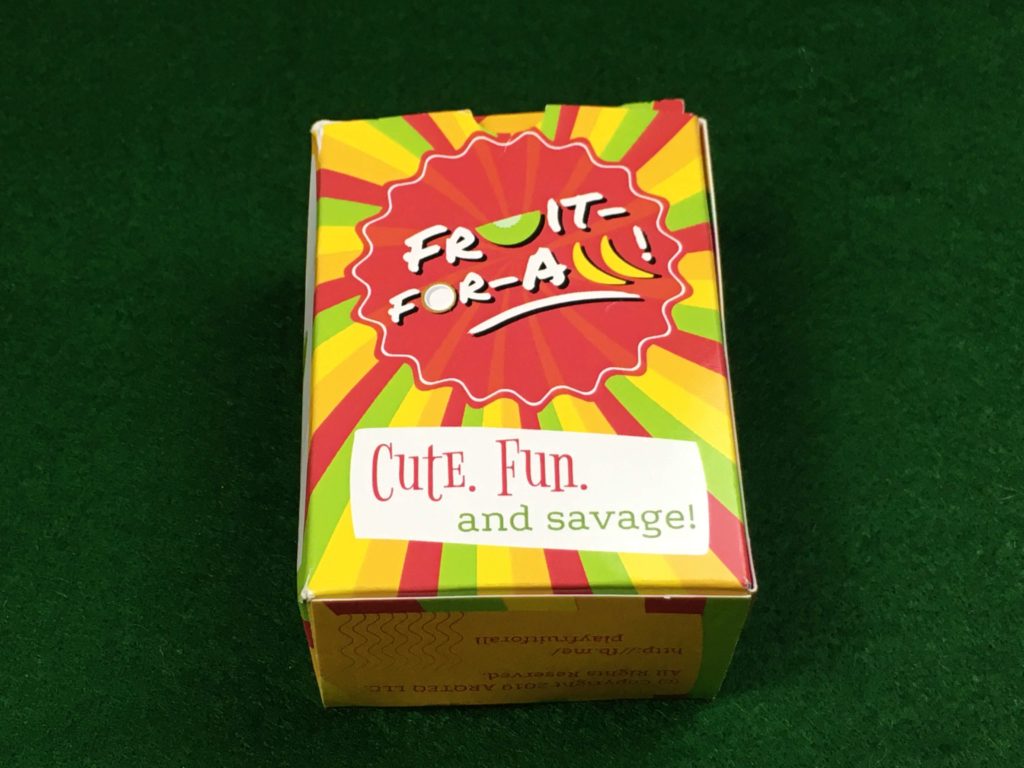

The front of the box has a fun, bright design. I like the way it looks like a giant pack of Juicy Fruit.

The back of the box has a quick overview of what to expect from the game play as well as the game stats.

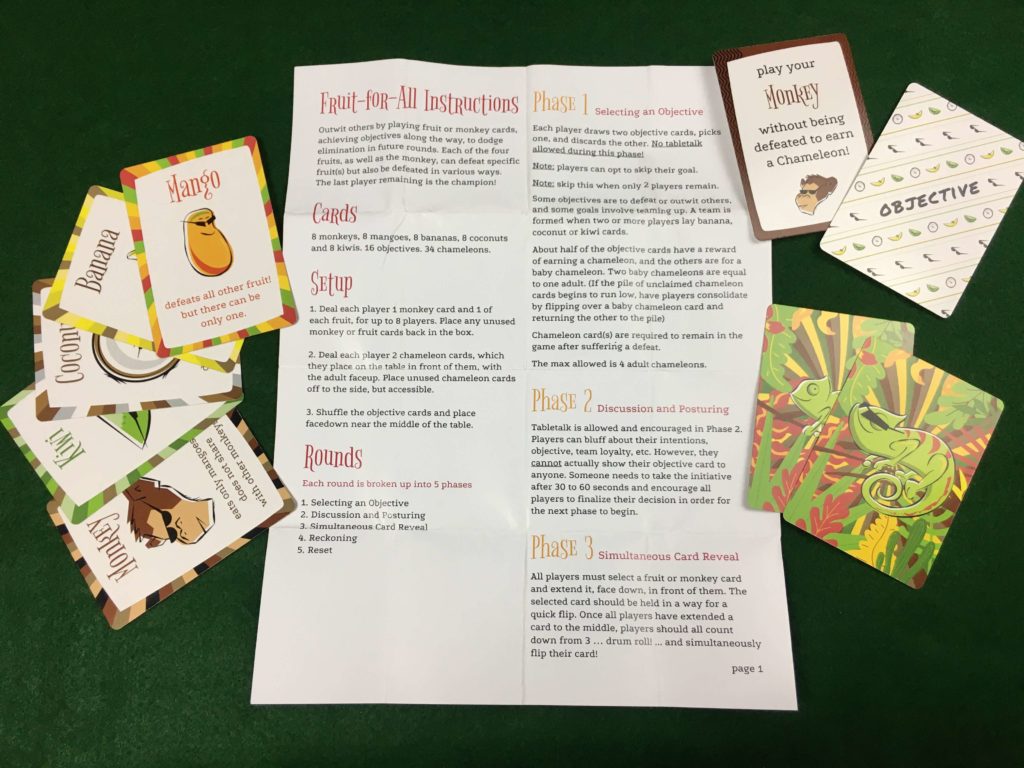

The rules are printed on the front and back of a single page document. The document is folded to the size of the tuck box and stuck behind the cards. It turned out to be a bit bulky, and I think it contributed to the bending of the box.

Another finalists in this contest used the small booklet for their rule book, and I thought it looked really sharp. It fits perfectly in the poker-sized tuck box and doesn’t show wear as easily as the document. I think that size of rule booklet could work great for this game, too.

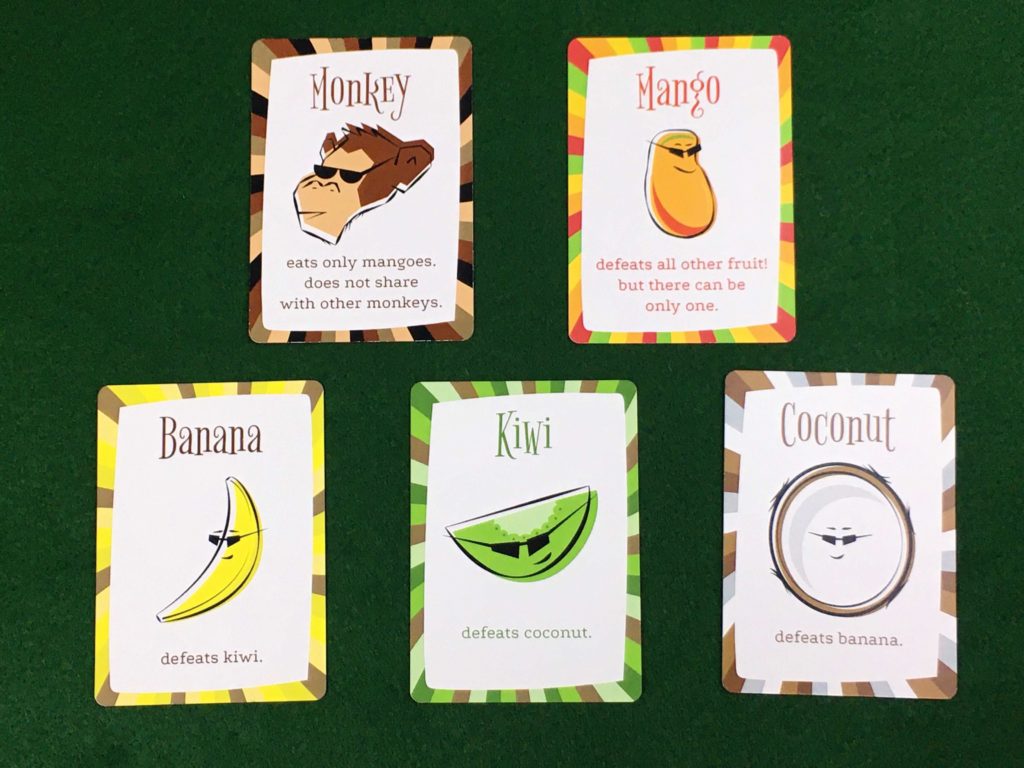

Each player has the same set of 5 cards: Monkey, Mango, Banana, Kiwi, and Coconut. The cards say on their faces which cards they defeat. Since we always had access to all 5 cards, they served the dual purpose of action card and player aid.

The box also includes a huge pile of chameleon cards. These are the cards that track a player’s remaining lives. One side of the card is a chameleon while the back is a baby chameleon. A baby chameleon is only half a life.

Each completed objective earns the player either a chameleon or baby chameleon depending on the difficulty of the objective.

There are 2 objectives related to each type of card in your hand, one set for generically teaming up on any basic fruit team, and one set for generically outwitting other players. Some of the objectives make you target a certain player such as the person to your left or to your right.

Everyone I’ve played the game with has questioned what “Outwit” is supposed to mean. These cards were the most confusing part of the game.

Overall, the cards look great with fun illustrations and nice font choices. They are easy to read and understand.

Game Play and Mechanics

The advanced Rock, Paper, Scissors mechanic in this game seemed a little confusing on paper, but it was easy to understand once we started putting it into practice.

After the simultaneous reveal, the different types of cards resolve in a specific order.

First, you check for Monkeys. They survive as long as there is a Mango to eat. If there are no Mangoes, anyone who played a Monkey loses a life. If there are an equal or greater number of Mangoes than Monkeys, all the Monkeys survive and all Mangoes lose a life. If there are fewer Mangoes than Monkeys, the Monkeys face off using the cards remaining in their hands until there are few enough Monkeys to allow each one to get an available Mango.

Next, you look at Mangoes. As long as the Monkeys haven’t wiped them out, Mangoes defeat all other fruit. However, if there is more than one Mango in play, all of the Mangoes lose a life and the other fruit survives.

Finally, you check for Bananas, Coconuts, and Kiwis. These form a regular Rock, Paper, Scissors circle, but there is safety in numbers. A smaller group of fruit cannot defeat a larger group of fruit. For example, Coconut beats Banana, but 2 Coconuts is not enough to defeat 3 Bananas. This would be a stalemate. 2 Bananas would be enough to beat 2 Coconuts, but it would still be a stalemate if there were also exactly 2 Kiwis on the table.

The objectives create a fun battle of wits that I might need more practice with before I fully understand. For example, I haven’t quite figured out what I should bluff if I get the objective to successfully play a Monkey card, but I think it makes for an interesting problem to puzzle out.

It could be helpful to specifically clarify how baby chameleons work in the rules. My understanding is that if you have only a baby chameleon left, you can stay in the game, but any time you have 2 baby chameleons, you forfeit both of them whenever you lose a life. The rules never explicitly say any of this, but it’s what seems most intuitive to me.

I like the idea of the Outwit cards, but the rules need to more clearly define what constitutes “outwitting” someone. Is it simply not losing a life in a round when they lose one? Do they have to have played the card you told them you wanted them to play? Does it have to be your card that lands the attack on them? What if you both lose a life but they did play the card you asked them to play? Do you still win a chameleon?

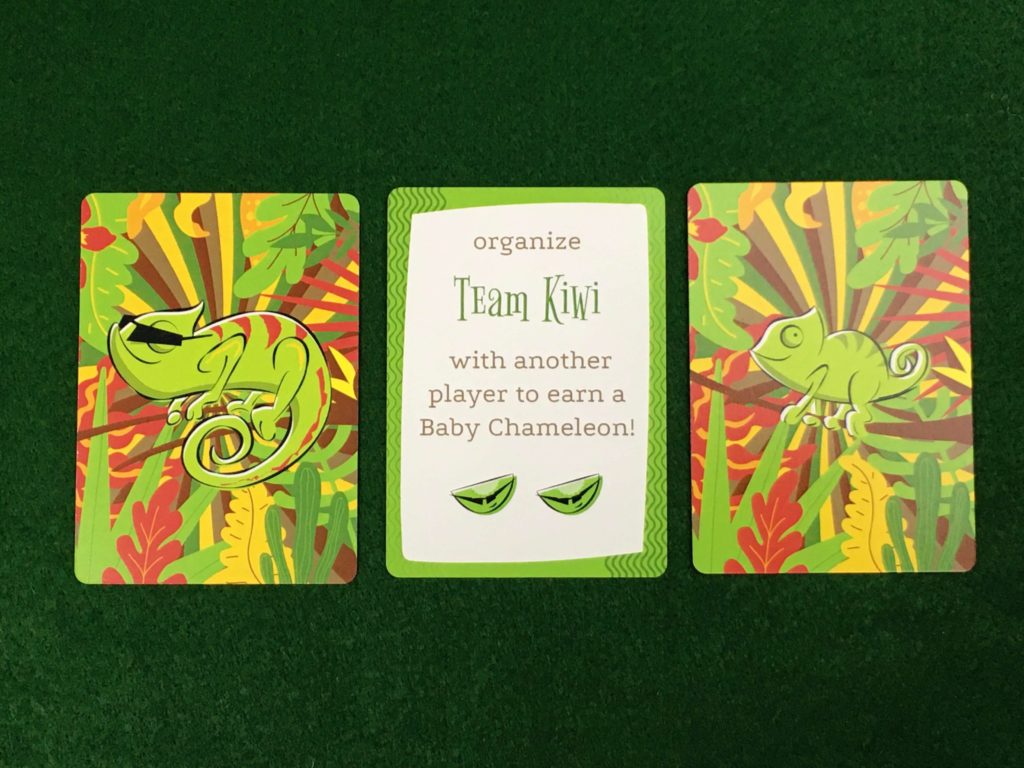

I think it would also help to better clarify the rules for objectives that say things like “Organize Team Kiwi with …” Some players said they thought you should only win the prize for these objectives if you were the first person to suggest forming the team. Others said it should mean that you said out loud before playing the card that you would be on the team (and actually follow through on playing the card).

In practice, I told people to take the reward for these objectives as long as they played the required card along with the correct number and/or seating arrangement of the other players with matching cards. However, a few of the cards simply say “team up” instead of “organize,” so I wasn’t 100% sure I was handling this rule correctly.

I was also unsure if it was supposed to be possible to complete an objective in a round where you also lost a life. It seems unlikely that this is supposed to be possible, but the rules don’t address this one way or the other.

My least favorite thing about this game was the player elimination aspect. Since you only start with 2 lives, it’s very possible you’ll only play 2 rounds before you’re stuck watching everyone else play until the end of the game.

The rules say 4 is the maximum amount of adult chameleons you are allowed to have, but there seemed to be way more chameleon cards than we were ever likely to use. It might be nice to start with 3 chameleons instead of 2 so that you have a little time to recover if you get off to a bad start. I also wonder if it could work to play a set number of rounds (maybe 4?) and no player elimination with the player who has the most chameleons at the end taking the win.

One play tester suggested bumping up the social deduction factor by assigning each player a role matching one of the cards from their hand (monkey, mango, coconut, kiwi, or banana) that they are never allowed to play. Then, each player could earn points for correctly guessing other player’s roles. Without play testing it, I’m not sure how well this would work in practice, but I did think it was an interesting idea.

If players could earn points for correctly guessing others’ identities, eliminated players would have something worth observing after they are out, which could be a nice feature.

Scoring

The following scoring breakdown is based on a rubric I released during the game design challenge on TGC’s contest page. All sections are worth a maximum of 1 point.

Balance: 1

As far as I could tell, everyone in the group felt like they were on an equal playing field. While some of the objectives might be trickier to pull off than others, since everyone gets a new objective each round, one turn with a difficult objective doesn’t feel like a disadvantage in the game overall.

Originality & Creativity: 1

This game took the familiar concept of Rock, Paper, Scissors and added a couple of fun extra powers along with bluffing. The familiar aspects make it easy for new players to quickly pick up, but the extra twists make it feel unique.

Engagement – Down-Time: 0

When you still have lives left, the turns go quickly, and there isn’t much down time. However, it’s fairly easy to end up striking out after only 2 rounds, after which you will be waiting a while before the final winner is determined. Watching others play isn’t very interesting when you have no decisions to make yourself.

Engagement – Tense Interactions: 1

The negotiation phase is the meat of this game. It was fun to brazenly lie to one another and try to tell who was doing the same to you each round.

Engagement – Would Play Again: 1

This is the only game among the finalist entries that my game group requested to play just for fun — and I was happy to agree. When we played, I removed the Outwit cards from the objective deck as my one “house rule” change — but it’s an easy change to make.

Intuitive Components: 1

All of the components were easy to read and use for their intended purpose. They are also packed with bright cheerful colors that make it easy to get new players interested to try the game.

Game Time – Rules in under 10 min: 1

I had no trouble teaching this game and getting everyone started in under 10 minutes.

Game Time – Total Time under 90 min: 1

This game easily comes in under 90 minutes. I think you could likely play a best 2 out of 3 mini tournament in under 90 minutes as well.

Bonus – Thematic Tutorial: 0

The theme of this game was great, but there was no tutorial mode that used theme or story to help walk players through the process of learning how to play.

Total Score: 7/8 – 88%

You can see the scoring breakdown for all the semi-finalists and finalists in this game design challenge in my public scoring spreadsheet.

Credits

Thank You to my Protospiel Madison Play Test Crew

Gerry Hazen, Will Newton, Patrick Rauland, Jeff Swiggum, and Robert Wise

Wow, I can hardly believe it! Thank you so much for the very specific and thorough feedback, I can definitely use it to make Fruit-for-All even better. And hearing that your group wanted to play it “just for fun” made my day!

I can’t wait to see what’s next for this game, whether it is finding a publisher or crowd funding it myself. Either way, the experience has been so valuable and I couldn’t have done it without you and many others in this awesome community!

Congratulations on a well-deserved win!

I’m glad you find the feedback helpful. The judging process was an interesting learning experience for me as well.

I realize now looking at the contest page on The Game Crafter that this entry was the lowest-ranked semi-finalist I chose as a finalist. One fewer vote in community voting, and it might not have been a finalist at all — crazy!

Although I did consider using my right as a judge to rescue games that didn’t make semi-finals, I wasn’t willing to do that for any game I didn’t feel sure would win out in the final round over games that achieved semi-finals. And, it turns out, it was hard for me to accurately picture what it would feel like to play these games based on rules alone.

For example, the rules for Fruit-For-All sounded a little confusing to me when I could only read the PDF, but, once the cards were in my hands, everything clicked much better. There were other games I suspected would make more sense when I could read the cards, but that didn’t end up panning out.

As far as I can tell, you are not on Facebook (which is a life choice I can certainly understand and respect). If you want to stay off FB but keep participating in contests, I encourage you to partner with someone who can talk about your projects in related FB groups. That could help get you enough visibility to solidify a spot in future community voting rounds. Good game designs deserve attention — but they won’t get much of it if there isn’t someone starting the conversation!

I look forward to seeing what you’ll do with this game. To me, it seems like a great candidate for a Crowd Sale. 😉